Unsurprisingly perhaps, my answer to this question is both 'no' and 'yes'.

From the Compact Oxford English Dictionary:

religion • noun 1 the belief in and worship of a superhuman controlling power, especially a personal God or gods. 2 a particular system of faith and worship. 3 a pursuit or interest followed with devotion.

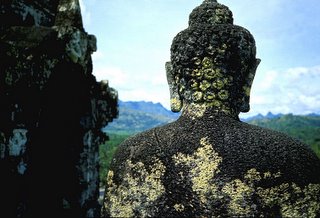

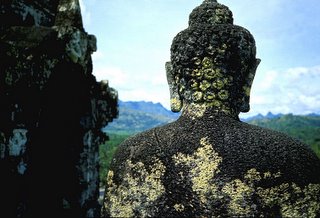

The enlightenment of Gautama Buddha was not a religious revelation. The order of monks that he established was not established to worship gods or even to achieve mystical union with them. The teachings of course included references to accepted religious and philosophical ideas - gods, rebirth and karma. But Buddha encouraged self-reliance over worship of the gods; he argued that all beings were subject to causal laws; he insisted that his path was for those who had such beliefs and for those who didn't. Buddhism is not a belief in a supernatural power. Buddhism is not about having beliefs - rather it is supposed to be a freedom from all views and a middle path between extreme views. The core of Buddhism is an acceptance of the Four Noble Truths, rather than any particular view on the afterlife or existence of divine beings.

However, Buddhism is of course classified as one of the major world religions and witnessing a Buddhist ceremony you would be likely to find many parallels and similarities with Christianity or Judaism. Millions of Buddhists around the world leave offerings for gods and spirits and dead saints. They have a belief in an afterlife which is supported by ancient dogma and many Buddhists, including Western converts argue for a need for faith and conformity to the Buddha Dharma. So, to some it might seem difficult to argue that Buddhism is not a religion like all the others.

It seems that the tendency to form religious belief systems is inherent in human nature. And to a fair extent this is what seems to have happened to Buddhism. Beliefs in spirits, gods,karma and rebirth/reincarnation were the cultural context that Buddhism arose in, and belief in these often constitutes what passes for Buddhism. Buddhism originated in a culture in which reincarnation, karma and the existence of gods were the standard explanations of the world we see. Even though Buddha often spoke in terms of such metaphysical explanations, Buddha's core insights (Dependent Origination, Anatta, Four Noble Truths) were not dependent on them.

Faith is important in Buddhism, but only in the sense that it is necessary to have confidence in the teachings, confidence built on personal experience and insight, like a climber's faith in his ropes and in the force of gravity. It's not the same as the blind faith in supernatural forces that characterises much Abrahamic religion and which they turn into a virtue. There are faith-based disciples and truth-based disciples of the Buddha and there are teachings appropriate for 'Eternalists' (those who believe in an eternal self) and for 'Annihilationists' (those who believe that the self is annihilated at death).

The reverence of Boddhisatvas seems to be a characteristic of Mahayana Buddhism which was not in the original Theravada practice.

What we know mainly by the name of 'Zen' in the West was far more minimalistic than previous forms of Buddhism, being much more focussed on the practice of meditation. Perhaps its development was a response to a Buddhism which consisted largely of giving offerings and prayers to gods and Boddhisatvas for good karma, chanting, memorisation of sutras.

There is a famous story of when Bodhidharma arrived in China after having sat in meditation in a cave for nine years.

Upon arrival in China, the Emperor Wu Di, a devout Buddhist himself, requested an audience with Bodhidharma (in 520 A.D.). During their initial meeting, Wu Di asked Bodhidharma what merit he had achieved for all of his good deeds for building numerous temples and endowing monasteries throughout his empowered territory. Bodhidharma replied, "None at all." Perplexed, the Emperor then asked, "Well, what is the fundamental teaching of Buddhism?" "Vast emptiness," was the bewildering reply. "Listen," said the Emperor, now losing all patience, "just who do you think you are?" "I have no idea," Bodhidharma replied. With this, Bodhidharma was banished from the Court.

An idea that Richard Dawkins proposes in his books is that of

memes as a basis for cultural evolution in analogy with genes and this idea is further developed by thinkers such as

Susan Blackmore and others. I think its a compelling argument, but exactly what the physical basis is of a meme is, is more ambiguous than the parallel case of genetic evolution. Dawkins proposes that many cultural entities can be seen as widespread simply because they are 'memeplexes'/meme-complexes, which are good at reproducing. He describes religions in this way, describing them as a 'virus of the mind'. They are not necessarily 'true' and not necessarily serving the best interests of the 'host', just prevalent because they are good at spreading. I recommend reading Dawkins' books to fully understand the argument, but

this article is a good introduction.

I find this argument an interesting way to explain some of the features of religion eg. the raising of blind faith over evidence to a virtue, but needless to say I can only see it as part of the truth.

These arguments are further developed by Susan Blackmore in

The Meme Machine. Interestingly Blackmore is a long-time practitioner of Zen. And she presents Zen with its detachment from belief and thought, its iconoclasm and 'kill the Buddha!' proclamations is really a memetic 'antiseptic' rather than a meme. I was persuaded that this was not just a matter of personal bias on her part although I'd suggest (and did by email) that Zen could be seen as an antidote to memes which is itself wrapped in a memeplex of its own. The 'raft' of the dharma is the memeplex, but Buddhism (correctly understood) aknowledges the provisional nature of this cultural vehical.

As you can see I tend to regard the religious aspects of contemporary Buddhism as rather dogmatic and unhealthy. While declining slightly in many parts of Asia, Buddhism is on the rise in the West - in some regions eg. Australia, Scotland and South-West England census data suggests that it is the fastest growing religion ('Jedi' doesn't count as an officially recognised religion, sorry :)). The two most popular sects are Tibetan and Zen. I'd suggest that many people drawn to Buddhism are are attracted by its anti-dogmatic traits compared with Christianity which has been on a slow decline in these areas for many years. Buddhism is in a process of adaptation for the west and I'd suggest that this is a good opportunity to cast off some of the dogmatic and religious baggage it has aquired on its travels.

I'm not the first westerner to suggest this of course - here are some links to individuals who are cutting away the cultural trappings in one way or another to reach through to the essenceless essence of Buddhism:

Brad WarnerStephen BatchelorChristopher CalderBut let's not forget that any desire we may have to adjust Buddhism to our tastes itself arises from our own modern cultural trappings.

To bring an understanding of Zen to Europe, Master Deshimaru talked as much in terms of 'God' as he talked about 'Buddha'. Yet, this wasn't a belief in a literal creator being or personal God - he was using the concept as a metaphor for 'the universal' or the fundamental principle of reality, not unlike the way that scientists like Einstein and Stephen Hawking use the concept.

To bring an understanding of Zen to Europe, Master Deshimaru talked as much in terms of 'God' as he talked about 'Buddha'. Yet, this wasn't a belief in a literal creator being or personal God - he was using the concept as a metaphor for 'the universal' or the fundamental principle of reality, not unlike the way that scientists like Einstein and Stephen Hawking use the concept.